Interlude [noun]: a short period of time when an activity or situation stops and something else happens.

If you’ve ever been to watch a play you will undoubtedly have had to sit through an interlude. Until recently, I saw this break in proceedings solely as a chance for the audience to go get some food, run to the toilet, or escape whatever theatrical horror they were being subjected to by their date. However, after a particularly long car journey, where ‘Stargirl Interlude’ by The Weekend came on my playlist, I began to question the purpose of the interlude not only in theatre but in the musical arena as well. With the nature of online streaming now you don’t have to wait for an interval to tell you to go to the toilet. You can just pause it. So why do so many artists utilise the interlude within their albums?

During a recent conversation, some light was shone on the situation. These theatre plays that last well up to three hours and tackle highly complex themes – try watching King Lea (worst school trip of my life) – bombard you with sensory stimulation. Keeping up with multiple characters, narratives and themes can seem almost impossible at times. Queue the interlude. More than just a chance to grab a bucket of popcorn, it offers a chance to process what you have experienced. The theatre’s generous hand reaches out, offering us a moment’s respite from whatever Shakespearian narrative we are witnessing, and in doing so we can truly enjoy all the nuances of the story. By taking a step back, even if it’s for a few seconds, we can better analyse the piece of media we are consuming, and in truly understanding it, its real value comes forward.

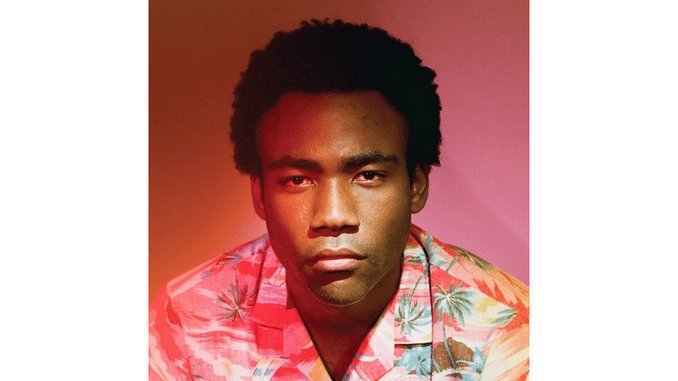

Generally speaking, this same purpose is utilised within music albums, especially concept albums which work to explore every nook and cranny of a particular theme or idea. Rather than weighing down the listener with a mountain of intricate ideas, a quality artist will place an interlude after climatic moments of discussion to offer some downtime to process. Donald Glover does this exceptionally on his 2013 record Because the Internet. An amalgamation of heavy, pulsating electronics, obscure vocal samples and thrashing lyrics, crash together to create a scorched soundscape intended to mirror the overwhelming nature of the internet age. ‘II. Worldstar’ delves into the impact satirical sites have on who we are as people and serves as a reminder that these sites act largely as a distraction. Then ‘II. Zealots of Stockholm [Free Information]’ questions the true motives of people based on their online presence in an ever-growing online world. With themes of existential dread and ego-death fuelled by an obsession with the internet, it is only natural that the listener at some point will scream out for a break during the albums track list, and that’s where ‘Dial Up’ serves a crucial role. A clunky windshield wiper beat (I’m serious) is paired with an infectious and glowing retro synth rhythm, creating an oddly peaceful and innocent aura in an album defined by themes of being jaded with the digital age.

Whilst this ‘break from proceedings’ style interlude is often used upon albums similar to how it is within the theatre, the creative scope of an interlude is widened drastically within the world of music, allowing musicians to effectively utilise it however they wish. There are no rules or expectations to the interlude. If an artist wants to make a track simply to proclaim how much they love themselves (looking at you Kanye…) they can. Who’s stopping them. For me, that’s the beauty of the interlude; the inherent ability to allow artists to truly express themselves outside of the boundaries of a song, often subtly adding to the sustenance and themes of an album.

So, upon closer inspection, I realised that the interlude can be used for a multitude of different purposes, and to stay with Kanye West for the meantime, one of the most effective is to heighten the dramatism of a particular moment. Kanye’s 2010 masterpiece, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, was released amidst a whirlwind of public criticism aimed at Kanye (a whirlwind that has resurfaced recently), and so the album served as his answer to the controversy that surrounded him. Crazy enough to believe he is the greatest to ever do it, the album staked his claim at the industry’s throne with an array of maximalist ideas and baroque style instrumentations. Every single track resembles a moment in hip-hop royalty, and to achieve such an extravagant sound, he utilises a specific interlude exceptionally: ‘All Of The Lights (Interlude)’. Appearing after ‘POWER’, an ode to Kanye’s relentless, exploding sense of self-worth, ‘All Of The Lights (Interlude)’ invites the listener to wallow in the nuclear fallout of what they have just heard, whilst also beginning another dramatic climb towards the albums most magnificent high, ‘All Of The Lights’.

When you have a record so abundant with fantastic tracks, oftentimes they don’t share the spotlight equally, as each one gets lost in the shadow of the next. Now of course Kanye, determined on demonstrating his genius, wants to place our undivided attention on every single track, and so he adopts interludes to yank our attention away from the previous masterpiece and build our anticipation towards the next, as he continuously shatters our already high expectations. ‘All Of The Lights (Interlude)’ offers a stark sonic contrast to ‘Power’. As ‘Power’ closes in a messy haze of electronics, the interlude ushers in a classical approach with merely a piano and violin. Slow dancing in perfect harmony these two instruments create a thick feeling of melancholy. This swift change from rampant invincibility to sombre vulnerability is the very archetype we have come to associate with Kanye West, and a perfect example of how interludes can quickly grasp our attention and instantly build our anticipation. This moment of juxtapositional softness within the album makes us ask: “what could possibly come next?”. The interlude prepares us for what is to come, refreshes our mind and avoids a clunky ‘cold open’ into the next track. Just as the violins wind down into a slumber, the iconic trumpet score of ‘All Of The Lights’ awakens. Kanye knew how great ‘All Of The Lights’ would become and refused to let it get lost within the shadow of ‘Power’. By using the interlude, he seamlessly builds towards another breath-taking climax on the album, without hindering the natural journey of the record.

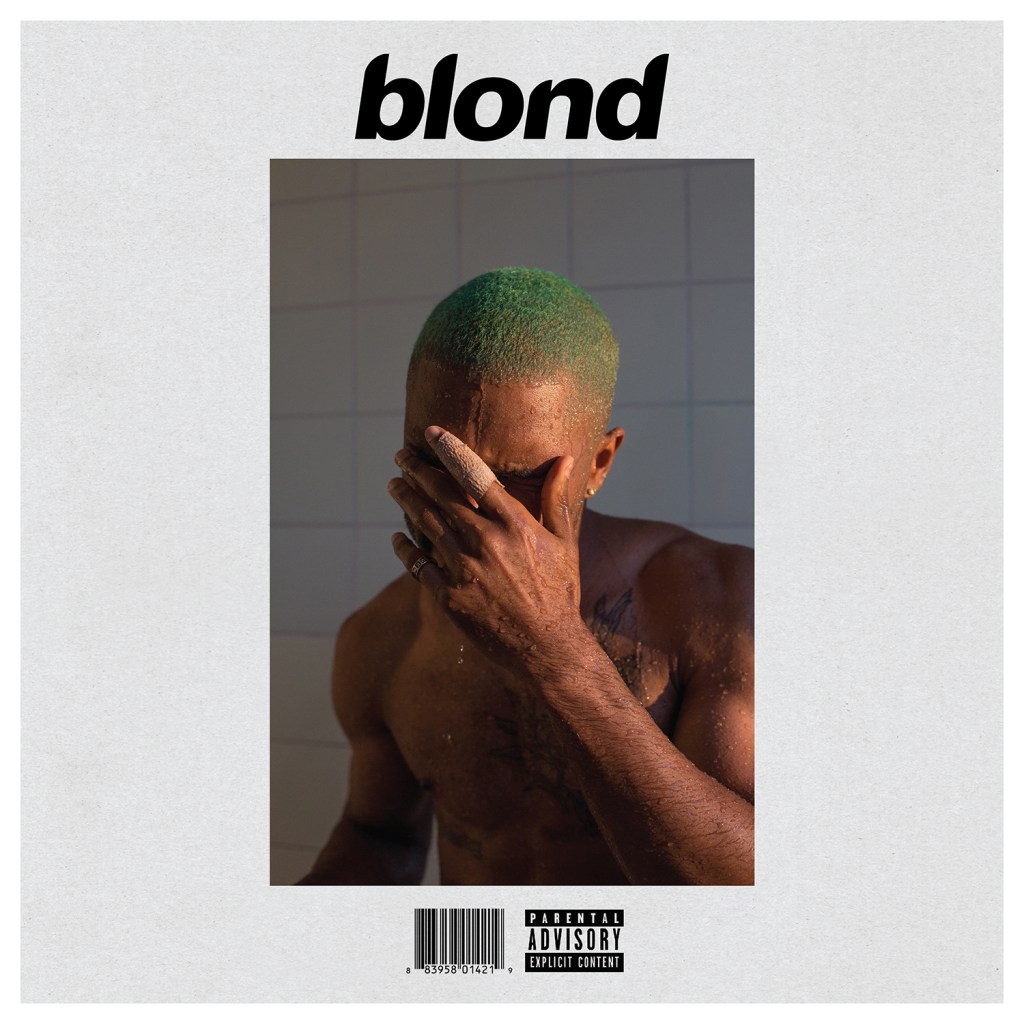

Bearing an unwavering transitional power, interludes have the capacity to encourage the seamless shift between songs, and when used correctly, the interlude heralds a new chapter in an album’s story. Mid-album interludes are by far the most common and well known. They come in all shapes and sizes and give an opportunity for the artist to show a bit of personality. These transitionary interludes can be anything, but are often musical breakdowns which reel you into the album’s story further, as it metamorphoses between themes. Frank Ocean has a moment on his album blonde where he wonderfully uses such an interlude to drive forward the record’s storyline and enter a new place of contemplation.

Ocean’s most vulnerable and personal project to date, blonde employs sexual experiences, loss and trauma to explore masculinity, depression and both the overwhelming ecstasy of love as well as its heart-breaking evanescence. Tremendously delicate, the album is precisely put together and Frank Ocean’s use of interludes mirrors such an approach. It may be known as just “that song before Nights” but ‘Good Guy’ plays a crucial role within the intricate storytelling of blonde. The first half of the track plays a brief lo-fi chord melody, accompanied by Frank’s raw vocals which laminate the decline of a fruitless sexual experience as he realises the intimacy they shared was meaningless. The gentle synthesiser in the background allows for Frank’s vocals to stand front and centre, putting his heart on his sleeve and thus, ushering in a new chapter in the album’s journey. It bridges the gap between the more romantic musings of Frank in the album’s initial half before tapping into his more cynical and darker guitar ballads of the latter half, starting with ‘Nights’.

Whether an artist uses interludes as an opening gag, a homage to a brilliant comedy show they watched, or a palate-cleanser, is entirely their artistic decision. Whatever the reason an artist made an interlude for (sentimental, cultural or otherwise), they can use them as they please, and that is their intrinsic beauty. No matter how they are used, they work to add sustenance to the album and plunge the listener into the carefully curated world that the artist has constructed. If you take the interludes out of an album’s track list and listen to them as stand-alone tracks, they most likely feel underwhelming and don’t make sense. Equally, an album without its various interludes loses its cohesion and falls apart into a non-sensical mess. It’s the little details that lay the foundations for the piece’s vastness to thrive.

Here’s a collection of my favourite interludes: